Asexuality and It’s Issues in YA Fiction

By Nashrah Tanvir

As an asexual reader, I see conflicting messages about the state of asexual representation in fiction and my heart hurts. Almost every list of recommendations, every discussion, and every moment includes a variation on the lament that there is so little representation with no elaboration or qualifications. There certainly is a lack of representation in fiction, there is also more out there than these articles often suggest and, though it makes little difference to the numbers as a whole, it can have a large emotional impact on individuals, especially those seeking asexual representation. Even if one restricts their search to books published by the Big Five companies in publishing- that is to say by imprints owned by Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Simon and Schuster, and Hachette- there is quite a bit more than people seem to assume. Though this assumption appears to be true only of YA books, outside these categories only a handful of books with explicit or deliberate asexual representation were published by Big Five publishers since The Bone People was published in 1984. Regardless, they are hard to find, especially for less internet-savvy readers or readers with access only to limited books.

As someone who not only got introduced to asexuality but learned to embrace it through books, representation in novels can be life-changing. It was Let’s Talk About Love and its cute interracial love story between a black, asexual woman and a Japanese man that made me realize why I’ve always dreaded sex scenes. Skipping sex scenes was my shameful secret. Meanwhile, every asexual person isn’t repulsed by sex, they sure take some time to understand why sex matters to others since they can’t experience sexual attraction or experience limited sexual attraction. Most asexual people begin noticing such differences of opinion between themselves and their peers around adolescence, so maybe in a way having a few asexual books targeted at readers from the ages of 12-18 is helpful. The book affirmed my belief in the existence of romantic notions without necessary sexual attraction. It was a strange validation. Pieces started fitting in as I realized I belonged to an asexual community too.

Heteronormativity played its trick to make me believe I’m straight for most of my life. It was a New Adult novel with a rather erotic setting called Red, White, and Royal Blue that first momentarily shook me out of my stance. The novel asserted that if you require convincing yourself that you’re straight, you probably aren’t. But doesn’t every straight person need a timely reminder about their sexual orientation? I soon dismissed the notion since it wasn’t a book I particularly enjoyed despite its great bisexual representation.

Every Heart a Doorway is one of the first mainstream books to explicitly use the term ‘asexual’ for one of its characters and has been one of the most prominent books with asexual representation in SFF since its release. It’s a quick read, however, doesn’t take the heavy task of explaining asexuality, unlike Let’s Talk About Love, which is okay since the burden of education shouldn’t be on a marginalized author’s shoulders. Fiction can often be eye-opening, but its purpose isn’t bit by bit education. But Every Heart a Doorway subscribes to the problematic practice of associating asexual people with death. All too often, asexual characters are depicted as estranged from society and as somehow bound to death and being dead. In a 2017 blog piece, Claudie Arseneault, author of The Baker Thief, charted these ties between asexuality and Western concepts of death and how “two of the most recommended books for ace fiction” closely associate with demise.

Another SFF book with well-defined terms of labels and feelings is The Sound of Stars which is a mix of romance and revolution. However, its issue lies not in the success of the representation of demisexuality, but at the same time in the degradation of aromanticism. Asexuality and aromanticism are often conflated but are different words with different meanings. Aromantic means someone who experiences little to no romantic attraction. The author of The Sound of Stars ends up pathologizing the absence of romance as an alien thing. Allonormative narratives often seem to seep in.

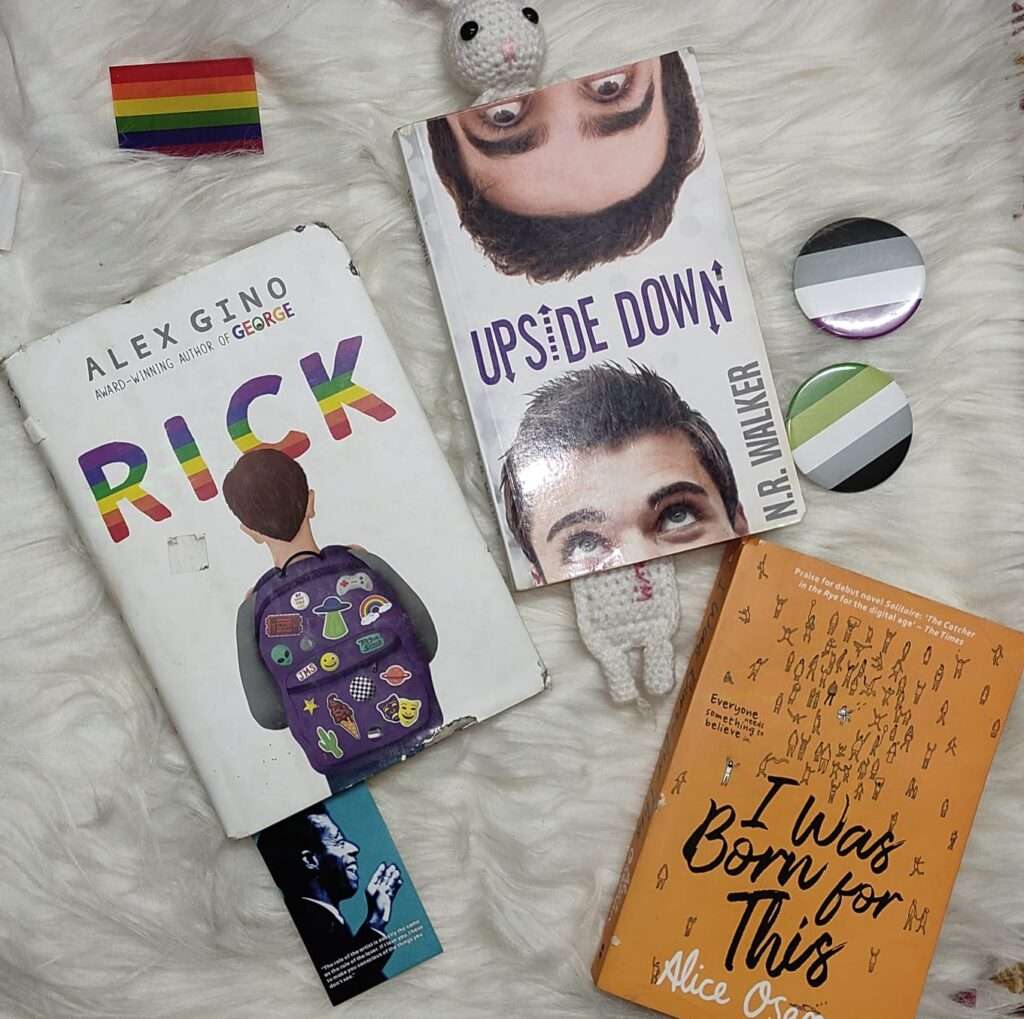

In one of the most popular aromantic asexual representations, Loveless by Alice Oseman, there’s a subversion of romantic troops such as grand gestures and confession of feelings in favour of spiritual love. It succeeds in celebrating different sorts of love from romantic to platonic to more. However, its character base largely remains white with tokenist BIPOC characters which in a way is okay since we should turn to BIPOC authors, not white authors, for BIPOC characters. However, many amazing representations of asexuality such as Aces Wild: a Heist, where the entire cast of important characters are asexual, and Bloody Spade, Which is an adventurous urban fantasy, remains white. It unfortunately backs up the view that asexuality is a white and foreign thing and becomes a gatekeeper for BIPOC asexual people. The existence of hypersexualization of black and brown women and feminine folks doesn’t help either. A recent New Adult release in college setting is set upon breaking race stereotypes as it introduces us to a Chinese aromantic asexual genderqueer protagonist who gets deep into an internet feud with the other aromantic asexual main character. It’s a slow-paced slice-of-life book that tackles reaction of different characters when they realize they’ve been taking relationship advice from two aromantic asexual people. However there is still work to do in exposing allosexuality, disrupting allonormativity’s complicity in racist regimes, and fully emancipating the radical potential of the YA imagination.

Exploring and affirming queerness in youth literature may unconsciously or consciously contribute to overlooking, neglecting, or even erasing asexuality in YA narratives. Its example can be derived from old books by Shaun David Hutchinson such as The Five Stages of Andrew Brawley which asserts that sex is a universal thing. Similar thing is portrayed in Things We Couldn’t Say which declares the existence of people who have sex as nothing but monks as a joke. However, as of recently Shaun David Hutchinson has started writing about asexuality and aromanticism in books such as The Apocalypse of Elena Mendoza, At the Edge of the Universe, and The State of Us. It can be seen that asexuality and the existence and experiences of asexual people disrupt both heteronormativity and homonormativity. At the same time, some narratives incorporated aspects of asexuality in books without it being the main point such as a straight asexual person seeking secret advice in Perfect on Paper and casual mention of the love interest’s demisexuality in Magic Mutant Nightmare Girl. It’s noteworthy since some books fail its asexual characters even when they’re the main ones. Seven Ways We Lie has splendid potential for representing autistic and aromantic asexual humans but by avoiding labels it conflates the two. Meanwhile, labels aren’t always necessary, and some books have achieved asexual representation without the use of specific labels such as Kaikye and The Siren, the Song, and the Spy, however, author of Seven Ways We Lie puts a specific focus on knowing the latter alphabets of LGBTQIAP+ community where she expands on pansexuality but never bothers with her aromantic asexual character who plays a limited role. Another book This Song is (Not) For You explores polyamorous relationship with an asexual person, however, one of the asexual character’s partners comments in secrecy that she wouldn’t have been with an asexual person if it wasn’t polyamorous dating, which is definitely fine but its expression is well meaningingly hidden from the said asexual character.

As noted earlier, even when there is explicit naming and recognition of asexuality, the practice of conflating sexual orientation with romantic orientation is still relatively widespread. Although an increasing number of YA novels do indeed acknowledge and explicitly identify the various romantic orientations of their ace and acespec characters, various recent YA novels conflate these orientations. For example, Before I Let Go, the protagonist’s romantic orientation is never identified or addressed. Again, this asexual character could be coded as aromantic due to her comments that she doesn’t get crushes unlike her classmates.

Another problem arises from allosexual character being set up as saviour for the asexual character from their isolation, ignorance, and feelings of brokenness in books like Dare Mighty Things and Tarnished are the Stars. When characters do appear who do not have sex or who seem uninterested in sex, they all too often are represented as villainous, aberrant, or broken in some way and portrayed as serial killers, aliens, mythical creatures, robots, or deeply damaged people who either have their lack of sexual interest used by the writers to show how strange or inhuman they are or are later ‘saved’ or ‘made whole’ by human emotion in the form of a romantic relationship and sex.

The difficulty in identifying asexual characters in YA fiction is complicated by the indirect ways in which many YA texts might talk about sexual attraction and sex to maintain the suitability of sexual content for teenage readers. The mixed success of YA novels’ sincere attempts to fully imagine queernormative futures for asexual as well as allosexual characters speaks to the persistence of allonormativity and that there is still work to do for YA literature to enact and sustain its potential for equitably representing asexuality and for problematizing and disrupting hegemonies of sexual differences.

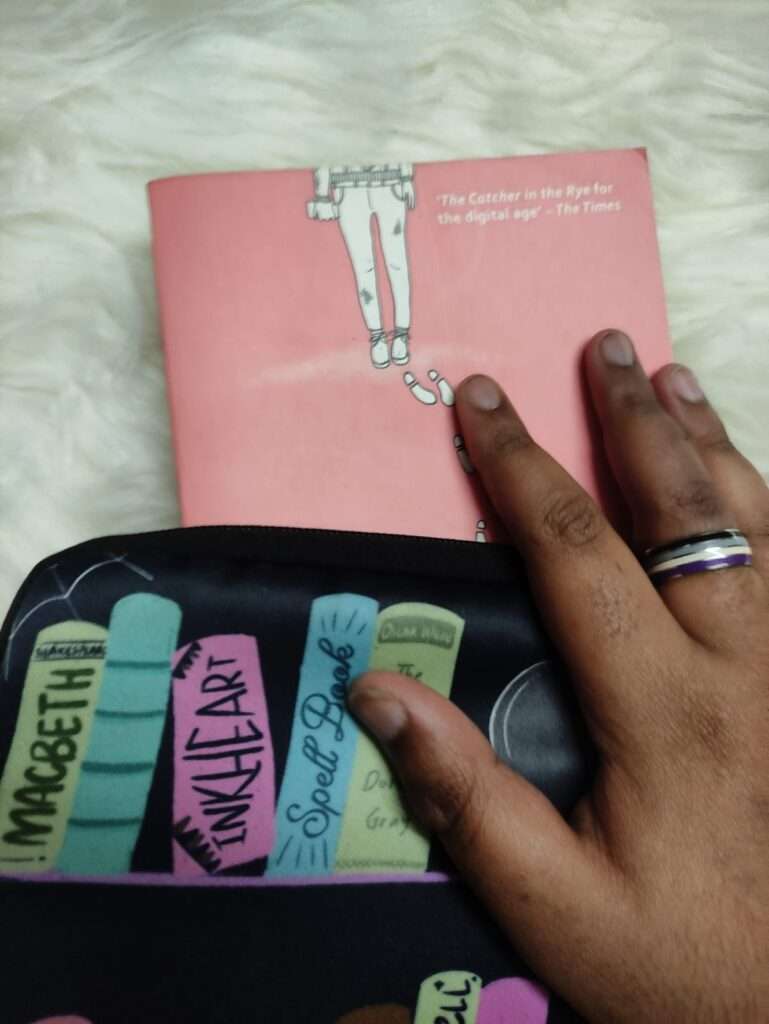

The views expressed in the article are the personal views of the writer. Image credits: Nashrah Tanvir

Nashrah Tanvir writes about mental health, feminism, and Islam. Her poems have appeared in The Hindustan Times, Magic Pot, The Teenagers Today, The Radiant, Gulmohar Quarterly, AZE Journal, DisLit Youth Literary Magazine, Poems India, and Wingword Poetry Prize. . She is an aro ace and credits books for questioning her sexuality.